The following is an extended version of an essay published in University of Melbourne Collections, no.10, June 2012, pp.15-23

- Installation image of Experimental Gentlemen, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 19 March – 25 September 2011. Photo by Viki Petherbridge.

There are both duties and obligations upon those of a civilized people who, for their own or their country’s advantage, enter a strange and almost empty land … Once a man is housed against weather, has food in the larder and can keep in touch with his neighbours, he has won to a position where he can begin to study his surroundings and satisfy the inborn curiosity that is the prime cause of man’s accumulated knowledge. The thoughtful man in a new country like this then, becomes aware of his obligations to his successors … No country has been so violently disturbed in its age old rest, and consequently in no country does the responsibility of preserving a knowledge of the past rest quite so heavily upon its people.

Sir Russell Grimwade[i]

Obligation is a common theme in the writings of Sir Russell Grimwade. It gained particular force in his later years, when the question of his own mortality caused him to linger upon the many privileges his life had accorded him. It is a central theme of the above-quoted preface, penned in 1954 to celebrate the centenary of the National Museum of Victoria, and it is equally evident in a lengthy, heartfelt letter of two years earlier, in which he declared his intention to bequeath his estate to the University of Melbourne:

I have been one of the privileged and fortunate ones who has had a long and happy life. The fact that we have not been blessed with children makes such a scheme possible, and it is an endeavour to express my gratitude to the country that has done me so well and made me so happy. I believe firmly in the principle succinctly expressed by Noblesse oblige.[ii]

The Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest was an extraordinarily munificent gesture, establishing the Miegunyah Press and bequeathing a trove of Australian artworks, rare books and archival materials to the university collections. From William Strutt’s painted masterpiece Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia, 1852[iii] down to personal correspondence with premiers and prime ministers, items from the Grimwade bequest count amongst some of the most prized of the university’s treasures. The generosity of this gift should not be measured in purely financial terms, but as the embodiment of an obligation that Grimwade held dear: his noble and civilised duty to preserve and record Australia’s history for future generations.

William Strutt, Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia 1852 1887, oil on canvas, The University of Melbourne Art Collection, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0038

This duty was, in part, motivated by Grimwade’s affinity for a version of Australian nationalism to which he felt a close familial link. This nationalism was not founded on images of swagmen, bushrangers and larrikins, but was a genteel brand that celebrated the pioneering efforts of explorers, pastoralists and industrialists: men like James Cook, John Macarthur and Grimwade’s own father, the industrialist Frederick Sheppard Grimwade. These interests are clearly reflected in the material that Grimwade collected, reaching its zenith in 1934, when he arranged for the purchase of ‘Captain Cook’s Cottage’ and its transportation from Great Ayton, North Yorkshire, to the Fitzroy Gardens in Melbourne.[iv]

We might today consider this to be an eccentric gesture, just as we might see Grimwade’s version of Australian identity as quaintly antiquated (or even chauvinistically anachronistic). Contemporary Australian history has been opened to many competing voices. It no longer offers a single, unified view of the past, but a multiplicity that recognises that our vision of the past is shaped by, and contributes to, our understanding of the present. Politically conservative, Russell Grimwade would most likely have bristled at such a postmodern conception of history, yet it is a current that I believe he intuitively understood. For if, in one way, the transportation of Cook’s Cottage embodied a very traditional view of history (the literal reconstruction of the past), in another way, it revealed a much more radical ‘faith in the imaginative work that can be performed with the raw materials of history’.[v] In the transplanted stones and mortar of Cook’s Cottage, Grimwade was attempting to bring the force of the past into present view, and in doing so, create a space through which the national narrative could be shaped. Likewise, by donating his collections of Australiana to the University of Melbourne, he hoped that future generations would continue to engage with this task. In an era in which the narratives of Australian nationalism are more often hijacked by the odious parochialism of Hansonism, the Cronulla riots, and racially motivated violence, the obligation upon thoughtful men and women to reconstruct the past in order to understand the present has never been more urgent.

From July 2010 to June 2011, I was the direct beneficiary of Sir Russell Grimwade’s desire for such engagement. Under the auspices of the Grimwade Internship at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, I had the opportunity to research the Grimwade collections and curate the exhibition Experimental gentlemen (Ian Potter Museum of Art, 19 March to 25 September 2011). In doing so, I hoped to use the boundaries of Sir Russell Grimwade’s collection, with all its pointed omissions and exclusions, not as a limitation to the stories that could be told, but rather as an epistemological opportunity. If Griwmade’s collecting passions revealed his explicit desire to reinterpret the present through the past (and vice versa), Experimental gentlemen drew attention to the ways in which our own vision is equally preconditioned. Most importantly, the exhibition contended that history is not disconnected from the present, finished and done with, conforming to Erwin Panofsky’s conception of the modern historical consciousness as ‘a phenomenon complete in itself and historically detached from the contemporary world’.[vi] Rather, as I believe Grimwade recognised, Experimental gentlemen posited that the past retains an inescapable imaginative pull on the present, a lingering force that shapes how we see the world. As William Faulkner famously opined, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’[vii]

Installation image of Experimental Gentlemen, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 19 March – 25 September 2011. Photo by Viki Petherbridge.

Through the use of exhibition design, text panels, and listening stations featuring contemporary music and interviews with songwriters including Don Walker (Cold Chisel), Kev Carmody, Gareth Liddiard (The Drones) and Mick Thomas (Weddings, Parties, Anything), Experimental gentlemen attempted to present the past as a continual process of discovery. The exhibition’s title was derived from the name given by ordinary seamen to scientists and intellectuals like Joseph Banks, T.H. Huxley and Charles Darwin, who accompanied explorers like Cook on their great sea voyages. The title also provided a useful metaphor to connect Grimwade to this colonial heritage. With varied interests that extended to astronomy, botany, photography, automobiles, history and environmentalism, Grimwade was very much a modern experimental gentleman. The exhibition included objects such as a beautiful timber cabinet made by Grimwade to house his collection of eucalypt specimens,[viii] along with his 1920 publication An anthography of the eucalypts, for which he provided both the text and the artistically arranged photographs.[ix]

Not only did this serve to connect Grimwade to his revered explorers, it also helped position the exhibition as an unfurling succession of encounters, continuing into the modern era. Rex Butler has argued that the discovery narrative—the act of literally seeing a place for the first time—is constantly replayed in Australian art and art history.[x] Reading Butler’s observation against the grain, Experimental gentlemen aimed to use this repetition to create the contemporary anew in each historical instance. Rather than seeing the past as a series of compartmentalised, completed events, Experimental gentlemen recast it as a succession of unfolding presents, coalescing from the colonial period into the contemporary moment. Entering the exhibition, the viewer was immediately thrown into the first-person role of the explorer, confronted with a text panel that offered the following spatial and temporal challenge:

Stepping ashore, the moist sand gives way gently underfoot, embracing the soles of your shoes. After nearly a year on ship, it is like a giddy caress to your weary sea legs. The shore is golden, reflecting the bright autumnal light with the sizzling clarity of finely wrought crystal. It catches your eye and you are briefly stunned. It is as though you have passed into a brand new world, a world of untamed novelty where every plant and animal seems to astonish and confound. Everything is different here. You have stepped into the antipodes, where the natural order is reversed and nothing is as it seems.

One of the first works encountered upon entering the exhibition was a singular treasure from the Grimwade collection: Alexander Shaw’s A catalogue of the different specimens of cloth collected in the three voyages of Captain Cook to the southern hemisphere (1787).[xi] This small, leather-bound volume is a compelling relic of Cook’s voyages, a rich reminder of the history of indigenous presence, and a thrilling portent to the stunning designs that would flower into the rich contemporary art movements of today.[xii] If these tiny swatches have the ability (like so much indigenous art) to look both forward and backward, they stand in stark contrast to European representations of the people who created them. Experimental gentlemen contained several depictions of indigenous people encountered during Cook’s voyages, including John Webber’s etchings The fan palm, in the island of Cracatoa[xiii]and Waheiadooa, Chief of Oheitepeha, lying in state,[xiv] as well as Francis Bartolozzi’s A view of the Indians of Terra del Fuego in their hut, which accompanied John Hawkesworth’s 1773 account of Cook’s voyage.[xv]

Installation view of Experimental Gentlemen, showing Francis Bartolozzi’s A view of the Indians of Terra del Fuego in their hut and Alexander Shaw’s A catalogue of the different specimens of cloth … Photo by Viki Petherbridge.

Bartolozzi’s engraving, which was created after a drawing by the fellow Florentine Giovanni Battista Cipriani, is a striking example of the ways in which European vision was altered by convention and imperial desire. James Cook visited Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago off the southernmost tip of South America, in 1869, less than five months into his first voyage of discovery. On board the Endeavour were two artists, Alexander Buchan and Sydney Parkinson. Unfortunately, Buchan died of a seizure shortly after the expedition left Tierra del Fuego. His few sketches from the voyage were passed onto John Hawkesworth, who had been commissioned by the admiralty to edit Cook’s journals into a publishable form. In Cook’s journal, the captain rather bluntly referred to the natives of Tierra del Fuego as ‘perhaps as miserable a set of People as are this day upon the Earth’.[xvi] Never having been to Tierra del Fuego, and under the spell of a neo-classical fantasy, Hawkesworth transformed Cook’s account into a rhapsodic hymn to the virtues of the Noble Savage.[xvii] So too was the visual representation of the ‘Indians’ of Tierra del Fuego distorted to suit prevailing tastes. Commissioning Cipriani to re-imagine the Fuegians in a neo-classical mode, they are depicted in elegant profile, lounging in restrained contentment, unsullied by the trinkets and excesses of modern concern. This vision is in marked contrast to Buchan’s original watercolour (held in the British Museum), which shows them as a dank, huddled mass of humanity, much closer to his captain’s assessment.

The representation of Cook as the paragon of empire was equally prone to distortion, as revealed in Francis Juke’s large etching A view of Owhhee, one of the Sandwich Islands in the South Seas (1788) after John Cleveley’s Death of Cook (1784). Juke’s etching, which conforms to the written accounts of Cook’s death, shows the captain as a heroic martyr for Pax Britannia. Under siege from warring natives, the hero turns to his men and gestures them to cease fire. In 2004, however, the original Cleveley watercolour was discovered in a private collection in Buckinghamshire. Rather than showing Cook as conciliator, it shows him leading the charge, with the bodies of several Hawaiian warriors strewn at his feet.The distortions of colonial vision were not, however, always a deliberate manipulation. In many instances they were the by-product of artists grappling with the challenges of representing the new world within the visual strictures of old-world convention. This tension famously animates the paintings of John Glover, who wrestled to reconcile the idyllic image of Europe with the wilds of Tasmania. Glover was represented in Experimental gentlemen with a literally transitional work, created in 1831 on the island of Porto Praya, during his voyage from England to Australia. Glover’s delicate watercolour Porto Praya[xviii] was displayed alongside works by his two eldest sons, John Richardson Glover and William Glover. We believe this to be the first time these three artists have been exhibited together since the 19th century.

Installtion view of Experimental Gentlemen showing William Glover, Untitled (Classical landscape with figures and animals crossing a bridge), 1830, oil on canvas, 79.9 x 115.8 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1997.0034, purchased 1997, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection. Photo by Viki Petherbridge.

While John Richardson Glover is relatively well known, William Glover is a much more mysterious figure. The second son of John Glover, William was born in Leicestershire in 1791, less than a year after John’s illegitimate first son John Richardson Glover. In 1827, William purchased 80 acres of land in Van Diemen’s Land, and in 1829 he sailed to Tasmania with his younger brothers Henry and James. William and Henry eventually took up land at Bagdad, north of Hobart, but their partnership was soon dissolved due to a personal disagreement. William had little luck in farming, and filed for bankruptcy in 1842, before moving to Melbourne where he lived out his days as a coachman, dying in 1870.

In Basil Long’s 1924 biography of John Glover, there are several mentions of William Glover’s artistic achievements. He is recorded as a drawing master in Birmingham from 1808, making him a prodigious young talent, and he is noted exhibiting alongside his father and brother at Old Bond Street in 1823 and 1824.[xix] Despite this documentation, the locations of William Glover’s paintings remain largely unknown; the large oil painting in the University of Melbourne Art Collection is one of only two works in Australian public collections, the other being a small watercolour in the National Library of Australia. The untitled landscape in the Grimwade collection, purchased in 1997 with funds from the Miegunyah bequest,[xx] was conserved for Experimental gentlemen, revealing a wealth of detail previously obscured beneath discoloured varnish (illustrated). Amongst the details revealed was a series of pseudo-Egyptian hieroglyphs, carved across the building to the right of the canvas. The presence of these hieroglyphs suggest that the painting depicts the flight of Mary and Joseph into Egypt, but this reading does not account for the mysterious presence of the other three characters in the painting, including the strange, hermitic John the Baptist-like figure near the centre of the composition.

Shown alongside the works of his father and brother, Glover’s untitled landscape tells a very different story in the development of art in Australia. John Glover holds a canonical position as the first artist to successfully capture the Australian landscape; despite being painted in Australia, William Glover’s landscape shows how persistent the forces that shape our vision can be. This is thrown into stark relief by John Skinner Prout’s Fern tree valley, Van Diemen’s Land.[xxi] One of the most under-appreciated colonial landscape painters, in 1960 Bernard Smith declared Prout to be ‘a prophet of taste in the visual arts’,[xxii] citing him as the first artist to be able to paint the Australian landscape free of the constraints of topographic accuracy. In Fern tree valley (illustrated) we see the veil of European vision slowly crumbling as the artist comes to terms with the expressive potential of the Australian landscape and his place within it.

John Skinner Prout, Fern tree valley, Van Diemen’s Land, c. 1847, watercolour, 74.5 x 55.5 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1993.0024, purchased 1993, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

It is hardly coincidental that this marks the precise moment when Aboriginal Australians begin to disappear from the represented landscape. As Australians began to shape their own identity in relation to this place, it became necessary to cast the original owners out of the visual record. Until this point, however, indigenous people are an inescapable presence in the colonial visual record. Drawing on the Grimwade collection, Experimental gentlemen was able to present a remarkably detailed account of the colonial representation of Australia’s indigenous inhabitants, starting with early works such as William Blake’s noble and elegant A family of New South Wales[xxiii] after a sketch by Governor Philip Gidley King, through the mockingly comic Wambela by the convict artist Richard Browne, [xxiv] and culminating in a series of extremely unusual pencil drawings of indigenous people of South Australia. These previously unidentified works[xxv] were discovered to be the preparatory drawings for the lithographic plates included in J.D. Wood’s 1879 book The native tribes of South Australia.[xxvi]Wood’s text, alongside pioneering works by George Taplin, Alfred Howitt and Lorimer Fison, signalled the genesis of Australian anthropology.

Installation image from Experimental Gentlemen showing Unknown artist

after Gottlieb Meissel, A stage with dead body c. 1879 and Samuel Thomas Gill, The Australian sketchbook, 1865. Photo by Viki Petherbridge.

This new interest in the customs and traditions of indigenous Australians was spurred by the emergence of orthogenetic theories of evolution in which Aboriginal culture was seen as an earlier stage in the teleological progress of human civilisation. Aboriginal culture was likened to an archaeological remnant of primeval man. Once contact was made with the more ‘advanced’ cultures, it was inevitable that this ‘primitive’ culture would disappear. Not only did this lead to a sense of urgency on the part of early anthropologists to record and collect ethnographic data for the information it could shed on the development of humanity, but it also inspired artists like George French Angas and S.T. Gill to create detailed visual records of indigenous dress, material objects and cultural practices. Angas and Gill documented these observations respectively in their lavish illustrated books South Australia illustrated (1847) and The Australian sketchbook (1865). Sir Russell Grimwade had an extraordinarily complete collection of colonial Australian illustrated books, including fine copies of both these important volumes.

In contrast to the detailed attention paid to traditional indigenous dress and custom in these volumes, S.T. Gill’s lithograph Native dignity offers a striking counterpoint.[xxvii] It is likely that Gill, like many of his contemporaries, saw indigenous Australians as part of a dying race, but I wonder whether this work was also intended as something of a critical commentary on the adverse impact of the encroachment of modernity upon both indigenous and non-indigenous subjects? Penelope Edmonds has argued that the colonial city was a charged site in which ‘issues of civilisation and savagery; race, gender and miscegenation were played out’.[xxviii] By the 1860s, images of indigenous Australians in the urban setting were increasingly rare, not because indigenous people were not present in Australian cities, but because their presence was a source of great anxiety amongst non-indigenous Australians. Beyond a simple racist stereotype, by picturing such a transgressive image of the urban frontier, Native dignity plays upon the full range of urban anxieties of about the non-indigenous colonial subject. Confronted with the realities of the urban frontier, the non-indigenous subject is forcibly cast into the role of both coloniszer and coloniszed. Although imbued with all the prejudices of its time, the very act of picturing this violence is, in a small way, an act of resistance against the imperialism of silence.

Samuel Thomas (ST) Gill, Native dignity 1866, lithograph, The University of Melbourne Art Collection, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0648

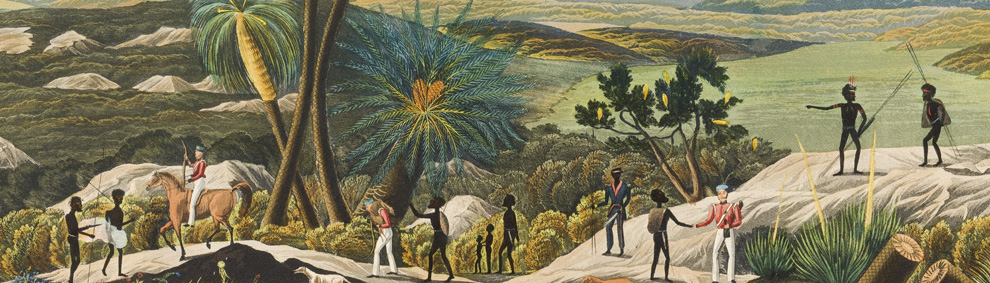

The propagandistic power of this silence is epitomised by Robert Dale’s impressive Panoramic view of King George’s Sound.[xxix] The panorama, which stretches nearly three metres in length, presents a series of detailed vignettes of the King Ya-nup people in their traditional country near the present site of Albany in Western Australia. In the most striking of these tableaux (illustrated in header), a group of British naval officers are shown returning from a hunting party with a group of King Ya-nup men. The leader of the British party, identified as Dale himself, is depicted shaking hands with one of the King Ya-nup. This scene paints the cross-cultural encounter between the British and the King Ya-nup as one of peaceful co-existence. At a time when British newspapers were filled with reports of violent indigenous insurrections, Dale’s panorama was a prime work of propaganda to entice settlers to the new colony. But the harmony of this scene masked a grim reality. In the booklet that accompanied the panorama, Dale wrote of the violent capture and murder of the indigenous leader Yagan, concluding with an ‘expert’ phrenological reading of the slain warrior’s skull, which Dale had taken back to London where it was displayed as an ‘anthropological curiosity’.

While the violence of this encounter seems at odds with our understanding of the present day, it is perhaps more important to note the tensions, contradictions and ambivalences that are at play in works like Dale’s Panorama shows that the relationships across cultures and between individuals are rarely straightforward. We can see this explicitly in James Taylor’s triptych view of The town of Sydney in New South Wales.[xxx] Despite its topographic style, it also served the propagandistic function of showing Sydney as a safe, industrious town in which the forces of darkness and light were in harmonious balance. Although intended to be a 360-degree view, the panorama runs left to right as an allegorical tale, from civilisation into barbarism. While the panels on the left and right are relatively obvious in their contrast, depicting cultivated Europeans at one end of the spectrum, and ‘primitive’ tribesmen on the other, the middle panel offers a greater conceptual challenge to the artist. In this panel, indigenous figures are shown as a strange hybrid, neither entirely European nor entirely other, dressed in peculiar, neo-classical togas. Terry Smith has described them as the ‘savages transformed’ of a utopian fantasy.[xxxi] Nevertheless, their presence in the middle of Taylor’s clearly ordered hierarchy reveals an inescapable tension between the dialectic of civilisation and barbarism. This tension is only partly resolved by the creation of the Noble Savage of Taylor’s imagination, which undoubtedly looked as implausible to viewers in 1823 as it does today.

Pointing to these ambivalences and uncertainties, where the rigid order of European vision came unstuck when confronted with the new world, is not to suggest that we are smarter, better informed, less racist or less blinkered than our colonial counterparts. Rather, it is to show that every present requires re-evaluation, revision, argument and debate. Questioning the ways in which our predecessors’ vision shaped their world is also to question how we see the world today, how our vision is shaped by the past, and how we wish to shape it for the future. Sir Russell Grimwade’s efforts to preserve the past in order to understand the present challenge us to consider how we wish to shape our own society. In taking up this task, we should not seek to preserve a single, unchanging vision of either the past or present, but one that is ready and open to the questioning of the scholars of tomorrow.

The Russell and Mab Grimwade Collection is held in the Ian Potter Museum of Art (www.art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/art_brow.aspx). The Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade Collection of books is in Special Collections at the Baillieu Library (www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/special/collections/australiana/grim.html) while archival records are in the University of Melbourne Archives (www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/archives/).

[i] Russell Grimwade, ‘Preface’, in R.T.M. Pescott, Collections of a century: The history of the first hundred years of the National Museum of Victoria,Melbourne: National Museum of Victoria, 1954, p. ix.

[ii] Russell Grimwade, quoted in John Poynter, Russell Grimwade, Melbourne University Press at the Miegunyah Press, 1967, p. 306.

[iii]William Strutt, Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia, 1852, 1887, oil on canvas, 75.7 x 156.6 cm. Reg.no. 1973.0038, Gift of the Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[iv] See Lisa Sullivan (curator), A collection and a cottage: Selected works from the Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest, University of Melbourne (exhibition catalogue), Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 2000.

[v] Chris Healy, From the ruins of colonialism: History as social memory,Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 35.

[vi] Erwin Panofsky, Meaning in the visual arts, New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1957, p. 4.

[vii] William Faulkner, Requiem for a nun, New York: Random House, 1951, act 1, scene 3.

[viii] Russell Grimwade, Timber eucalypt specimen cabinet, c. 1919–20, eucalypt with brass handles, 85.0 x 72.3 x 53.0 cm. Reg. no. 1973.0755, Gift of the Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[ix] Russell Grimwade, An anthography of the eucalypts,Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1920. Several copies of the original 1920 edition and one of the second (1930) edition are held in the Grimwade Collection, Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

[x] See Rex Butler, A secret history of Australian art, Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002, and Rex Butler, Radical revisionism, Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2005.

[xi] Alexander Shaw, A catalogue of the different specimens of cloth collected in the three voyages of Captain Cook to the southern hemisphere, London: Printed for Alexander Shaw, Grimwade Collection, Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

[xii] See for instance, Judith Ryan (curator), Wisdom of the mountain: The art of the Omie, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2009.

[xiii]John Webber, The fan palm, in the island of Cracatoa, 1788 (published 1809), hand-coloured etching, 44.1 x 32.7 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1973.0525, purchased by the Department of History 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xiv]John Webber, Waheiadooa, Chief of Oheitepeha, lying in state 1788 (published 1809), hand-coloured etching, 32.6 x 45.0 cm (plate). Reg.no. 1973.0523, Purchased by the Department of History 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xv] John Hawkesworth, An account of the voyages undertaken by the order of his present majesty, for making discoveries in the southern hemisphere, 3 vols, London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773. Grimwade Collection, Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne.

[xvi] James Cook, quoted in Bernard Smith, European vision and the South Pacific, London: Oxford University Press, 1960, p. 22.

[xvii] Hawkesworth, An account of the voyages,vol. 2, p. 59.

[xviii]John Glover, Porto Praya, 1831, watercolour (sepia wash) on paper, 3 sheets: 6.1 x 13.0 cm; 6.9 x 11.5 cm; 7.5 x 12.7 cm. Reg. no. 1996.0014.001.003, purchased 1996, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xix] Basil Long, John Glover, London: Walker’s Galleries (Walker’s Quarterly,no. 15, April 1924

[xx]William Glover, Untitled (Classical landscape with figures and animals crossing a bridge), 1830, oil on canvas, 79.9 x 115.8 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1997.0034, purchased 1997, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xxi]John Skinner Prout, Fern tree valley, Van Diemen’s Land, c. 1847, watercolour, 74.5 x 55.5 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1993.0024, purchased 1993, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection

[xxii] Smith, European vision and the South Pacific,p. 228.

[xxiii] William Blake (engraver), Philip Gidley King (artist), A family of New South Wales 1793, engraving from John Hunter, An historical journal of the transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, John Stockdale, London, 1793, Special Collections, Baillieu Library, the University of Melbourne, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973

[xxiv] T. (Richard) Browne, Wambela, 1820, watercolour and gouache, 31.0 x 23.0 cm (sight). Reg. no. 1992.0012, purchased 1992, the Russell and Mab Grimwade Miegunyah Fund, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xxv]Unknown artist after Gottlieb Meissel artist, A stage with dead body c. 1879, pencil preparatory sketch for the lithograph Stage with dead bodies from JD Woods (ed.), The native tribes of South Australia, ES Wigg and Son, Adelaide, 1879, The University of Melbourne Art Collection, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0372. Unknown artist after Bernard Goode photographer, A camp of Aborigines at Point Macleay c. 1879, pencil preparatory sketch for the lithograph Native encampment from JD Woods (ed.), The native tribes of South Australia, ES Wigg and Son, Adelaide, 1879, The University of Melbourne Art Collection, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0371

[xxvi] J.D. Woods (ed.), The native tribes of South Australia, Adelaide: E.S. Wigg and Son, 1879.

[xxvii] S.T. Gill, Native dignity, c. 1855, lithograph, 31.4 x 22.5 cm (image). AccessionReg. no. 1973.0648.005, gift of the Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xxviii] Penelope Edmonds, Urbanizing frontiers: Indigenous peoples and settlers in 19th-century Pacific rim cities. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010, p. 12.

[xxix] Robert Dale (artist), Robert Havell Jnr (engraver and publisher), Panoramic view of King George’s Sound, part of the Colony of Swan River, 1834, steel engraving, aquatint and watercolour, 16.5 x 211.7 cm. 1973.0225, gift of the Russell and Mab Grimwade Bequest 1973, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

[xxx] James Taylor (artist), Robert Havell & son (engravers), The entrance of Port Jackson, and part of the town of Sydney, New South Wales 1823, The Town of Sydney in New South Wales 1823, Part of the harbour of Port Jackson, and the country between Sydney and the Blue Mountains, New South Wales 1823 aquatint, engraving and watercolour, The University of Melbourne Art Collection Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0381–83.

[xxxi] Terry Smith, Transformations in Australian art, vol. 2: The nineteenth century – landscapes, colony and nation,St Leonards, NSW: Craftsman House, 2002, p. 22.