The following review was first published in Art Guide Australia, January/February 2011, pp.45-48. Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route was held at the National Museum of Australia (Canberra) from 30 July 2010 till 26 January 2011.

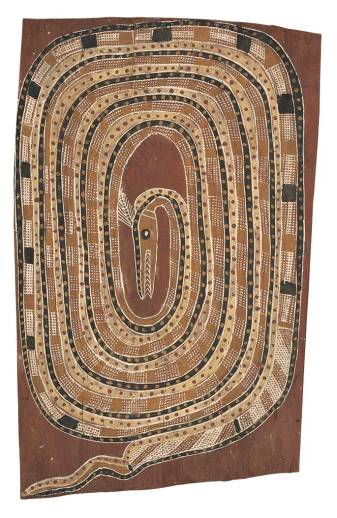

Jan Billycan, Kiriwirri 2008 acrylic on linen, 79.5 x 59.5 cm

Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route, currently on display at the National Museum of Australia is a remarkable exhibition. It arose from a relatively simple premise to explore the Indigenous histories underpinning the lands traversed by the Canning Stock Route. It evolved into a groundbreaking partnership between FORM, the National Museum and nine remote Indigenous art centres, amassing an incredible repository of hundreds of paintings, tens of thousands of photographs and dozens of hours of video footage.

Like everything about the project, Yiwarra Kuju is the result of an exhaustive process of community consultation. Just as the project sought to uncover the previously maligned Indigenous histories of the Canning Stock Route, the exhibition seeks to alter the museum experience in order to give Indigenous voices authority within the hallowed cultural realm of the museum. This is certainly a lofty aim, and Yiwarra Kuju has set something of a new benchmark for community involvement in the museum sector. And yet, as with any project this ambitious, it inevitably raises as many questions as it answers.

Central to these questions is the sheer pragmatics of how to present an Indigenous voice within the museum context. To this end, Yiwarra Kuju has opted for a number of bold curatorial interventions. Some of these are simple gestures, such as the decision to hang paintings of the Seven Sisters story near the ceiling, so that one is forced to crane skywards in order to view them; others signify profound philosophical attempts to challenge the classical museum experience.

Nora Nangapa, Nora Wompi, Bugai Whylouter and Kumpaya Girgaba, Kunkun 2008, acrylic on canvas, 124.5 x 294 cm

The most startling of these is the overwhelming amount of support material on display in Yiwarra Kuju. The gallery spaces are simply bursting at the seams with text panels, video displays, text panels, photographs, text panels, multimedia displays and more text panels. In the lavish catalogue accompanying the exhibition, the artist Clifford Brooks declares:

We wanna tell you fellas ‘bout things been happening in the past that hasn’t been recorded, what old people had in their head. No pencil or paper. The white man history has been told and it’s today in the book. But our history is not there properly. We’ve got to tell ‘em through our paintings.

But despite Brooks’ faith in the veracity of painting, the 80 works in the exhibition are accompanied by literally thousands of words of text. The effect is so overwhelming, that one often feels that it is the paintings that are the support material, and not vice versa. Certainly, the aesthetic elements of the works are consistently downplayed in Yiwarra Kuju, and at a recent forum in Melbourne, the co-curator John Carty was at pains to stress, “It’s not about the art.” This raises the inevitable question, why use art as the bedrock for an exhibition that is ostensibly historical in focus?

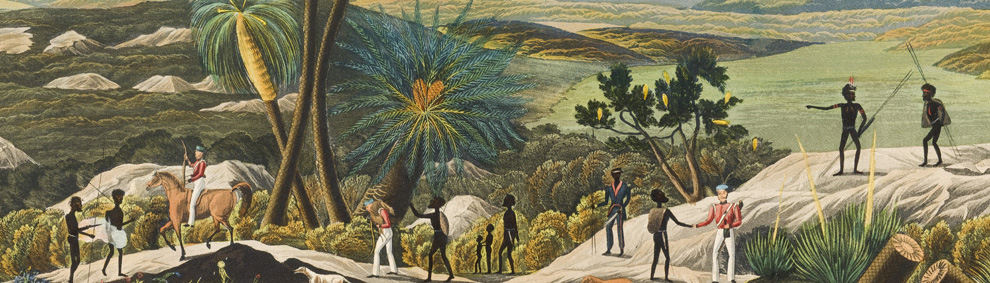

At the heart of this is a question of cross-cultural engagement. The Canning Stock Route was not a traditional Indigenous passage, but was artificially forged between 1908-1910 by a team led by surveyor Alfred Canning. Cutting across the country of several different cultural and language groups, it was like a colonial scar that paid no heed to the pre-existing borders of traditional ownership. And yet, after its short life as a stock route, the Canning Stock Route was soon appropriated by Indigenous people to facilitate their own movement across country. By using the Stock Route as the locus for the exhibition, Yiwarra Kuju offers a complex double-take, eloquently described by community representatives Ngarralja Tommy May, Putuparri Tom Lawford and Murungkurr Terry Murray as a “two ways” story. On the one hand, the exhibition is all about tradition (the pre-existing ownership and stories that underpin the country the Stock Route bisects), on the other, it is a story about change, adaptation and engagement.

Painting provides the perfect metaphor for this cross-cultural story, presenting a unique testament to the stunning marriage of tradition and innovation. Unfortunately, this is a concept that only gels in a few salient points in Yiwarra Kuju. In part, this is due to the extraordinary democracy of the hang, in which most works are evenly spaced along two black walls, arranged, not according to style or visual affinity, but according to content, in a long run that is intended to replicate the process of crossing country. This curatorial decision creates inevitable visual tensions. There is a massive disparity of both styles and quality across the exhibition, and in many cases, works with similar content are not necessarily visually complimentary. The uniform dramatic spotlighting serves some works well, but it is inappropriate for others, particularly more subtle works, which get lost in the glary haze.

This rejection of traditional notions of aesthetics is symptomatic of the rejection of what are perceived as Western art historical values. This leads to a profound failure to recognise the cross-cultural dialogic work that these paintings already perform. Standing before the most stunning paintings in Yiwarra Kuju – such as those by Rover Thomas, Daisy Andrews or Jarren Jan Billycan – it is difficult not to be taken aback by these artists’ individual ability to create dynamic new visual languages for expressing ancient stories, and in doing so, to take their culture forward in dynamic an unexpected ways. The juxtaposition of related artists painting related stories about related places in vastly different styles raises inevitable questions about the diaspora of style in Western desert painting and the historical and social forces that have shaped its development. This invokes notions on the role of representation, the nature of cultural change and the changing role of aesthetics in Indigenous society.

Rover Thomas, Canning Stock Route 1989, ochre and natural binders on canvas, 105.5 x 60.5 cm, Holmes à Court Collection.

These are necessarily art historical questions that demonstrate the urgent need for new cross-cultural methodologies for Indigenous art history. Yiwarra Kuju: Canning Stock Route offers the first, imperfect steps towards a model of engagement in which Indigenous artists are able to present their history and culture in the manner that they best see fit. This should not mean that it is above criticism, but that it becomes part of an essential ongoing critical dialogue. Perhaps the most exciting thing about the Canning Stock Route project is that with the acquisition of the entire collection by the National Museum of Australia, it will become a permanent resource for future Indigenous artists, curators and historians. Over time, hopefully it will yield many more exhibitions, and through continued engagement with the collection, reveal many more as yet uncovered stories.