Below is the extended version of a review that first appeared in Art Guide Australia, January/February 2010

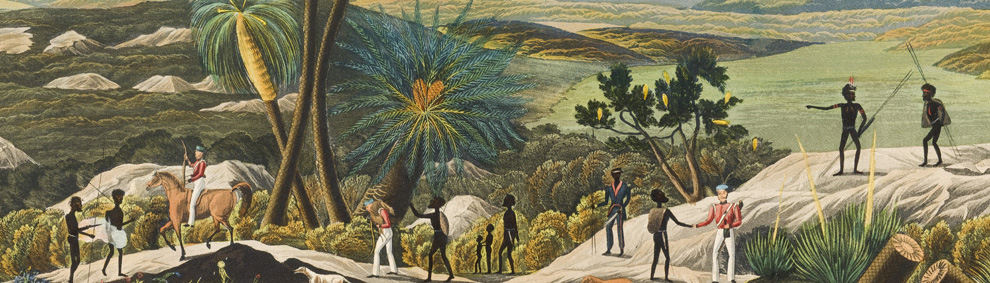

As the Indigenous art movement has developed in Australia, it has continually been refreshed, renewed and reinvigorated by the appearance of new, elderly artists. Whilst this has been something of a unique feature to Indigenous art, it follows a certain internal logic. It is these older artists who remain closest to the pre-colonial cultural traditions which make Indigenous art unique, and, as Indigenous culture places a premium on seniority, it is these ‘elder’ artists with the greatest cache of cultural knowledge to draw upon. The Indigenous art market, in particular, has helped reify the notion of ‘elder’, making it a common refrain of commercial gallery sales pitches, in which each and every geriatric Aboriginal artist is carefully positioned as a profound repository of arcane spiritual and cultural knowledge.

Unfortunately, this simple reification of age does not accurately reflect traditional Indigenous power systems, which are based on far more complicated stratifications of ceremonial knowledge, clan affiliations, gender, custodial rights and responsibilities. The reduction of cultural seniority to the egalitarian category of ‘elder’ fails to recognise the personalities and backgrounds of individual artists. Just because an artist is elderly, it does not necessarily follow that they are an Elder in a ceremonial, custodial or leadership capacity.

This may seem like a pedantic point – particularly in relation to an exhibition as gloriously celebratory as Emerging Elders (National Gallery of Australia, 3 October 2009 – 14 June 2010). And yet, it points towards a profound disjunction between traditional Indigenous cultural and aesthetic values, and the art market. On the one hand, the market supposes to hail the continuation of culture – celebrating Indigenous art for its ‘stories’ and cultural knowledge. On the other hand, it is often not the most culturally important works or artists who are most popular in the marketplace. In some instances, senior artists work is considered too ethnographic or rigidly traditional for a market which prefers bold, individual expressionism. In other cases, the more culturally knowledgable artists work across too many styles or stories – something which gives them great kudos amongst their peers, but is less attractive to a marketplace that favours easily identifiable ‘trademark’ designs.

These are questions that overshadow the reception of Indigenous art. They are questions in dire need of address if non-Indigenous Australians are to begin to have any meaningful engagement with Indigenous art. They are not insurmountable questions, but ones which require a patient, careful and considered cross-cultural dialogue on aesthetics and value.

Despite being evoked in the exhibition’s title, however, these urgent questions are not answered in Emerging Elders. First and foremost, Emerging Elders is a celebration of contemporary masterworks from the National Gallery of Australia’s collection. Like the Gallery’s 2007 Triennial of Indigenous Art, it lavishly showcases the institution’s ongoing commitment to collecting and exhibiting the finest examples of contemporary Indigenous art. Indeed, many of the nation’s leading artists are represented with major works. Gulumbu Yunupingu’s shimmering bark paintings of Garak, The Universe make a majestic centrepiece to the exhibition. And yet, their presence inevitably causes one to question the category of ‘emerging’. Gulumbu is a former winner of the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, her designs adorn the ceiling of the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris and in 2006 she was awarded the Deadly Award for Visual Arts. By every possible standard, Gulumbu is an established and major figure in Australian art. The same could be said of many of the artists in Emerging Elders – such as Ningura Napurrula, Shorty Jangala Robertson or Dorothy Napangardi – who have all had long and distinguished careers. Others seem to have emerged to the very point of over-exposure, such as the prolific Bentinck Island Elder Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, who has been a ubiquitous presence in recent Indigenous art exhibitions.

But perhaps more confusing, is the inclusion of artists whose position as ‘elders’ seems less assured. Anmatyerre painter Billy Benn Perrurle is represented with a monumental depiction of his homelands Artetyerre, whose glissandos of overlapping brushwork brilliantly reveal his development from a painter of small, delicate landscapes into a rugged, De Kooning like expressionist. In another room, a large canvas by Tiwi artist Timothy Cook shows the artist finding a new maturity – balancing his typically idiosyncratic sense of form with the addition of fine over-dotting. The work retains the raffish charm of Cook’s early paintings, but tempers it with a sense of cosmological delicacy. And yet, whilst both works are indisputable highlights of the exhibition, as outsider artists, neither Cook nor Benn properly fit the mould of ‘elder’ in the sense of cultural knowledge, leadership or responsibility. Both artists belong to communities from which there are both older and more culturally senior artists. One surmises, they have been included for their artistic rather than cultural pre-eminence. In this sense, they seem to fit neither categories of ‘emerging’ nor ‘elder.’

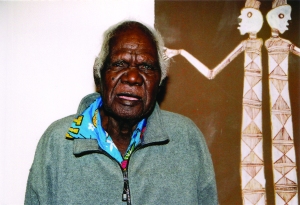

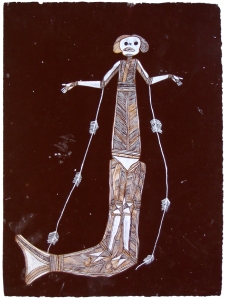

It is the artists who fit most comfortably into both categories whose voices speak most commandingly in Emerging Elders. Born in 1928, Harry Tjutjuna of Ernabella is represented with a spectacular depiction of the Wangka (Spiderman) Tjukurpa. Glowing in an incandescent haze of orange, red, yellow and black, it is like a grand, pop-art rendering of an ancient Dream. It speaks with a bold visual inventiveness that asserts its presence and the authority of knowledge it contains.

Other works speak just as authoritatively, but in a hushed voice, whose gentle overtones whisper of a different time and place. Kimberley elder Alan Griffiths painting of dancers engaged in the Mindarr and Waringarr ceremonies bristles with the action of a giant carnival while locking into an ancient schemata that fills it with a still, silent nostalgia for past times. Elizabeth ‘Queenie’ Giblet’s Pa’anmu (Headbands) for Laura Festival (above) evokes a faded memory of ancient ceremonial markings through her understated and elegant use of grey, black and white. These works conjure the air of a passing epoch – a time when the ceremony ground would fall silent in anticipation of the Elders’ command. And yet, they also show the continuing power of this voice in contemporary art. They show how the Elders’ voice can continually emerge, to be reshaped into dynamic and relevant contemporary statements. It is these works with the power to once again strike us silent with awe.