In July, that State Library of Victoria will be hosting an exhibition of works by the colonial Australian artist ST Gill. The exhibition, Australian sketchbook: Colonial life and the art of ST Gill, is being staged to coincide with the launch of a major new book by Professor Sasha Grishin of the Australian National University. Grishin has been researching Gill’s work for several decades now, so Grishin’s book, ST Gill and His Audiences promises to be a major contribution to the field. Grishin will also be presenting at a one-day conference, along with many other distinguished figures.

I became interested in Gill’s work while curating the exhibition Experimental Gentlemen at the Ian Potter Museum of Art. I included a number of Gill’s works in the exhibition, including a copy of the Australian Sketchbook after which Grishin’s exhibition is titled. I had an idea for a longer piece, which never quite made it over the line to publication, but which I thought I might offer here, more as a series of rough thoughts than a finished argument. I am sad that I won’t be able to be in Melbourne for the conference, because I think that Gill’s work presents a lot of complex questions in relation to how the Australian colonial imagination was formed.

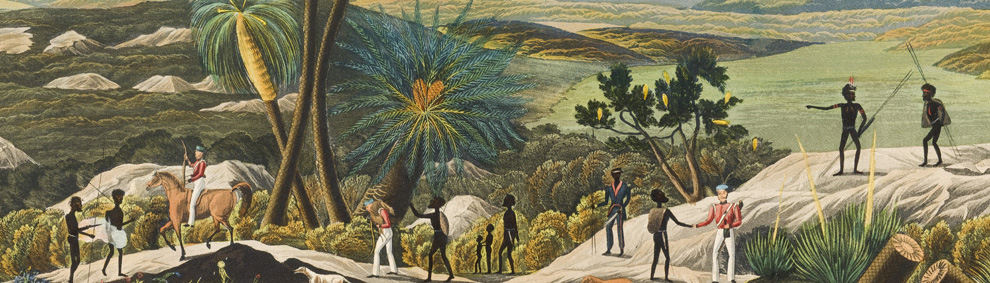

The State Library of New South Wales holds one of the largest collections of paintings, prints and drawings by the Australian colonial artist Samuel Thomas Gill (1818-1880). Amongst its collection is a pair of small watercolours designed to be viewed in concert: a technique that Gill frequently used to tease out subtle antinomies across his satirical scenes. The first of these scenes, entitled The Newly Arrived c.1860, shows a group of European settlers dressed in top hats and frock coats, gathering around an Aboriginal family. In the centre, an Aboriginal man in a long flowing fur-skin coat, and his naked son, perform a spirited dance for the onlookers. So enthralled are the new settlers by this exotic performance, that one man reaches into his hip pocket, presumably for some coins to reward his primitive entertainer. In the background, a row of neat brick houses suggests a well-established and thriving colony.

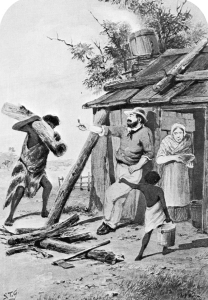

The second image offers a stark contrast to the genteel pleasantries of The Newly Arrived. Gone are the neat brick houses and gentlemanly finery; in their place, a shanty bark hut and the rough and tumble uniform of the pioneer settler. Likewise for the Aboriginal characters: the life of carefree dancing as exotic amusement is replaced with a heavy burden, as they are roped into the hard labour of empire building. With his characteristically acerbic satire, Gill titles this second work The Colonized c.1860

It is hard not to read these two works as “before-and-after” shots, contrasting the carefree life of Australia’s Indigenous inhabitants before being colonized, with their subjugation under the imperial project. But there is also a charged ambivalence to this contrast: not only does Gill offer a vague sympathy for the plight of his Aboriginal subjects, but he simultaneously points towards the degradation of colonial settler subject-hood: a fall from grace that effects the European on the frontier, himself colonized as part of the imperial process. While the European in The Colonizer is appears to be the “master,” it is a debased mastery, devoid of the fine trimmings of civilized society.

The frankness with which these images explore colonial encounters across the Australian frontier makes The Newly Arrived and The Colonized are remarkable pair of images. Lynette Russell argues, that while the American frontier was lauded by writers like Frederick Jackson Turner as being responsible for the emergence of an American identity, in Australia, “the frontier was essentially ignored.”[i] Ian McLean takes this further, suggesting that the frontier acted as a vital negative component to identity construction, habituating an inability to feel “at home” in the new country. According to McLean, for Australian artists, the frontier could not be pictured because it defied temporal unison. American painting could transcend this, because it was freed from colonial attachment, but in Australia the frontier was too close. The Australian artist was caught on the cusp of two worlds.[ii] As Paul Carter notes, picturing the act of settling became a psychic impossibility for Australian artists, requiring the constant proliferation of boundaries, whose deferral served the “symbolic function of making a place that speaks, a place with history.”[iii]

The Newly Arrived and The Colonized might be seen as both exception to, and proof of, this psychic impossibility. If by setting these two images against each other, Gill draws explicit attention to the passage from settling to settled, from colonizing to colonized, at the same time, it is a passage that occurs in absentia. The precise moment of colonization is never pictured, remaining always an invisible passage; even the transaction of payment alluded to in both works, is never visually realized.

This essay is not an attempt at what Rex Butler has called ‘radical revisionism.’ It does not seek to re-write history from the perspective of the present, in order to show the artists of the past pre-empting the political and social concerns of our current age. In addressing the work of ST Gill, I do not wish to position him as a radical proto-post-colonialist, speaking across “time-like separated’ areas to contemporary issues” or articulating “newer public virtues of beauty, persuasiveness and social justice.”[iv] My ambitions are decidedly more modest: my argument is that the art of ST Gill illustrates a key transitional moment in the development of the Australian colonial imagination, when the temporal strategies of modernity (such as historicism, evolution, and nationalism) emerge to normalise and repress the inherent contradictions and instability of the colonial project. By a fortunate confluence of coincidences (including his genre, audiences, temperament, and historical moment) Gill inadvertently captures this fleeting moment of transition, and in doing is, pictures the ambivalence of colonial discourse before it is obscured beneath the redemptive nationalist fantasy of the Heidelberg school of Australian Impressionism.

If, as Homi Bhabha has argued, uncovering this ambivalence serves to disrupt to destabilize the colonial project, this should not in any way be considered an act of rebellion on Gill’s behalf. Despite the ways in which it is often read, I understand Bhabha’s text as offering a method of interpretation and not a strategy of resistance. As he notes, disclosing the colonial ambivalence is a process that serves to both normalize and disrupt colonial authority.[v] Rather than being actively subversive, if Gill’s work reveals the antinomies and inconsistencies of the colonial mission, it is because it all too faithfully visualizes the colonial frontier without the benefit of the strategic apparatuses that would soon serve to normalize the unstable systems of power relations upon which this mission was founded.

In large part, this disclosure is the necessary result of Gill’s picturing of the urban environment, as opposed to the landscape idiom that dominates the canonical narrative of Australian art history. As Penelope Edmonds argues, colonial frontiers did not exist only in the bush, backwoods or borderlines. Rather, as the site for the emergence of colonial modernity, it was the “urban frontier” in which the realities of colonial authority were most conspicuous.[vi] Despite imperial confidence in the spatial order of the city and its power to produce and discipline subjects, colonial cities were mixed, uneasy, and transformative spaces, shaped by settler-Indigenous relationships. Torn between imperial ambition and colonial anxiety, they were the primary “contact zone” (to use Mary Louise Pratt’s term) in which issues of race, gender and miscegenation were played out. Edmonds notes that colonial cities were charged sites of mutual transformation in which the colonial narrative and identity was confounded and subverted. “Just as Indigenous people were colonized, so too were the newcomers and new spaces indigenized, albeit in highly uneven ways and within asymmetrical relations to power.”[vii]

It was in these urban encounters that the ambivalence of colonial relationships was brought into starkest relief, casting the settler subject as both colonizer and colonized. Following Lefebvre’s edict to reveal the ways in which spaces obscure the conditions of their own production, Edmond’s argues that settler cities have become naturalized and inevitable, concealing the constitutive relationships of Indigenous dispossession and displacement that adhere in their current incarnations.[viii] In examining Gill’s images of the ‘urban frontier,’ I would like to suggest that it was precisely this transactional, transformative nature of colonial cities that made them such heightened sites of colonial anxiety, leading most Australian artists to ignore the city in favor of the idealized bush. By exploring the slippages in Gill’s urban scenes, this paper aims to reveal the motivations and inherent repressions that underlie the development of the colonial imagination, and reveal the ideological foundations of Australian colonial identity.

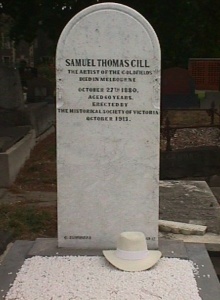

It was late in the afternoon of Wednesday 27 October 1880. Rounding the corner of Bourke and Elizabeth Streets, the artist S.T. Gill collapsed onto the steps of the Melbourne Post Office. In full public view, the once famed ‘artist of the goldfields’ died in quiet anonymity from a ruptured aorta: his heart finally broken from years of heavy drinking. As ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ entered its decade of greatest prosperity, one of its most important chroniclers was buried in a pauper’s grave, his passing marked only by an indifferent note in the Sydney Bulletin, commemorating “an artist formerly well known in the South.”[ix] A century later, in his monograph S.T. Gill’s Australia, Geoffrey Dutton lamented, “Even now, Gill is an under-rated artist.”[x] By 1981, however, this seemed a somewhat outdated threnody. As early as 1911, A.W. Greig had begun Gill’s critical resurrection with a lengthy piece in the Melbourne Argus asking, “Are there any Victorian’s alive to-day who, for the sake of his art and the sake of the days that are gone, would rescue the last resting place of poor “S.T.G” from the oblivion to which it has fallen?”[xi] Within a year, the Historical Society of Victoria had relocated Gill’s remains to a private grave with a handsome headstone bearing the inscription: “Samuel Thomas Gill – The Artist of the Goldifelds.”[xii]

There seemed little doubt that Gill had been welcomed back into the Australian cultural canon: his works were acquired by all the major public institutions in Australia, and his reputation as ‘The Artist of the Goldfields’ was reaffirmed in every major Australian art historical text of the twentieth century.[xiii] By 1971, in the very first monograph on the artist, Keith Bowden marvelled, “High prices are now paid for [Gill’s] pictures and his books have become scarce collector’s items, all steadily appreciating in value and all eagerly sought.”[xiv]

For Dutton, however, it was not simply a matter of prestige or prices, but the seriousness with which Gill’s work was inserted into the narrative of Australian art history. As the title of his monograph suggests, this was connected to a peculiarly nationalist narrative, in which artistic development (like colonial settlement) was an unfolding process of acculturation, that Anne-Marie Willis has described as “coming to terms with the uniqueness of the land, learning to love it, leaving behind their European aesthetic framework an seeing the Australian landscape ‘with Australian eyes.’”[xv] This was not simply an aesthetic development, but a psychic process of identity construction. Thus, according to Dutton, it was Gill’s temperamental sympathy for the “Australian” characteristics of egalitarianism and “rough democracy” that attuned him to the “Australian” experience, allowing him to see the landscape as it really was. “As if by osmosis,’ writes Dutton, ‘Gill was at home from the time he stepped off the boat.”[xvi]

His ardent poetic and sympathetic temperament, spiced with a humour that could detect the hidden balances of character and occasions, enabled him to be wide open to the Australian experience … in a few year, he was already the most Australian of the 19th century artists, speaking the instinctive language of Australia’s rocks and trees, wildflowers and light.[xvii]

If these boosterish claims lack a certain level of sophistication (particularly in their evocation of a singular ‘Australian’ experience), they are hardly unique to Dutton: his is merely one iteration of a common refrain in Australian cultural history, in which the landscape is used to naturalize what Willis terms “illusions of identity.”[xviii] According to Willis, in such narratives the landscape is endowed with an inalienable truth, the problem being that of the observer, “needing to remove the scales from their eyes in order to see the land fully revealed.”[xix]

Nature is posited as culture, when in fact, nature itself is a cultural construction and the history of Australian landscape painting is not one of progressive discovery, the building up of an ever more accurate picture, but a series of changing conceptualizations, in which one cultural construction plays off another in ever more complex webs of invention and in which the picturing of the local intersects with other, including imported, aesthetic and cultural agendas.[xx]

Leaving aside for one moment the constructed nature of this narrative as critiqued by Willis, the question remains: why, despite the best efforts of critics like Dutton, has Gill’s work continued to sit so awkwardly within this nationalist narrative? This inexorable quandary confronted Bernard Smith in his pioneering 1945 history of Australian visual culture, Place, Taste and Tradition. Like Dutton, Smith concluded that “the most Australian of all artists, though himself an Englishman, was Samuel Thomas Gill … In many respects he was more Australian than any of the Heidelberg School.”[xxi] Recognizing that this flew in the face of art historical orthodoxy, Smith defends his position in an extraordinarily prescient passage that anticipates Willis’ argument made half a century later:

It will be said that Gill’s work was only Australian in content, that the form was English. But where a racial or national quality is to be found in a work of art, in our times, and belongs to the Western European tradition, such quality almost invariably resides in the content … A prevalent form of aesthetic snobbery has seen fit to use certain qualities of the Australian landscape – the nature of the trees, skies and fields – as Australian symbols. The reason for this is to be found, perhaps, in the Impressionists’ preoccupation with landscape painting, and on the other the squatter’s idolization of his property. There is no such thing as an Australian art-form. Lines and colours have no nationality … Gill used a style typical to the English graphic artists of the early nineteenth century to portray Australian genre subjects; Streeton used the formal qualities popular among the academic Impressionists of the late nineteenth century to portray Australian landscape subjects. Both expressed local subjects with techniques developed abroad, and in doing so both assisted the movement towards a national style, since content always tends to create a pattern suited to its own expression.[xxii]

In Place, Taste and Tradition, Smith offers the first social history of Australian art. In drawing attention to the Heidelberg Impressionist’s use of the landscape as national symbol, he pre-empts the critiques of scholars like Willis and Richard White, who argue that by linking national character to landscape, the Heidelberg artists naturalized Impressionism as a style. “It was a myth invented by the Heidelberg school,’ argues White, ‘that theirs’ was the ‘first truly Australian vision’ – their commitment to naturalism required that all previous versions were contrived.”[xxiii]

By 1961, when Smith set himself to writing the history of Australian painting, his commitment to Gill as an artist of distinctly “Australian character” posed a number of difficulties. Not least of these was reconciling Gill’s work within the dominant trope of melancholy that, following Marcus Clarke, Smith argues defines the Australian landscape tradition. Thus, on the one hand, Smith asserts that Gill’s paintings “form a most valuable commentary upon the life of the time, a commentary which is expressed with great gusto and great humour,” making Gill the first artist to “express the sardonic humour, the nonchalance and the irreverent attitudes to all form of authority, so frequently remarked upon by the students of Australian behaviour.”[xxiv] On the other hand, Smith is quick to remark that this humour is always tempered by the “melancholy of the Australian scene … the dead and fallen timber, the stunted grass-trees … the presentations of the dramatic in a primeval setting.”[xxv]

The dominance of the landscape narrative in Australian art history is tellingly revealed in the subordination of the scene to the setting that occurs in Smith’s account. Equally revealing is his invocation of the primeval quality of the landscape; by 1980 Smith had begun to recognize melancholy as a vital trope occluding the guilt of terra nullius.[xxvi] It was Smith’s student, Ian McLean who would take this idea to its logical limits, framing melancholy not as an ailment, but as a linguistic meta-trope underpinning the thought and imagination of the entire colonial epoch.[xxvii] For McLean, this melancholy created a dialectic narrative of redemption and failure, allowing for the creation of history from loss. If melancholy serves to dehistoricize the landscape, it also finds in it an original landscape that substitutes for the migrant’s actual sense of loss. “A melancholy landscape,’ he argues, ‘is an historical landscape, haunted with memories.”[xxviii]

In pointing to this melancholy, both Smith and McLean draw attention to the challenge that the proximity of the Other on the frontier posed to the structured order of European selfhood. Frederick Jackson Turner would unwittingly point to these antinomies in his influential 1893 treatise, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” For, if Turner’s “frontier thesis” is best know for the proposition that it was the endless space beyond the frontier that forged the aspirational nature of the American character, he also recognized the frontier as the site of encounter: “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.”[xxix] It was through the hardships and adversity of this encounter that Turner believed a truly unique identity would emerge: “the outcome is not the old Europe [but] a new product that is American.”[xxx]

Turner’s evolutionary approach to American history stood in stark contrast to those who saw the frontier as merely a site where culture was replicated over an ever-expanding territorial domain.[xxxi] Half a century earlier, Alexis de Tocqueville contended that the cities of the New World were constructed from the “invisible luggage” of their migrant settlers. The men who travelled to the American wilderness, he argued, brought with them “the customs, the ideas, the needs of civilization” and implanted them in the wilderness.[xxxii] Despite their differences, however, in framing the frontier as a dividing line between civilization and wilderness, both Turner and de Tocqueville cast the frontier as a psychic line demarcating the limits of European identity. As Paul Carter concludes, this required a particularly western logic of property value, in which territorial units were treated as isolated legal and economic units.[xxxiii] Not only did this set the preconditions for the atavistic principles of origin and territory upon which western identity was based, but the endless deferral of the expanding frontier also enabled the developmental drive of capitalist modernity.

While the frontier provided the site for exposure to the Other, thus extending identity, this demarcation allowed a beyond in which the Other could be cast as contrary, maintaining the illusion of a stable identity.[xxxiv] The way of achieving this beyond was temporal.[xxxv] Rod Macneil has argued that understanding the landscape as temporal Other was fundamental to its recreation as a space available for colonization. Cast in primeval terms as the dialectic counter to civilization and modernity, the wilderness was forced to play a psychic role as the baseline against which colonial history could be written in order to stem the tide of ahistoricity. Couched in the terms of progress and redemption, the consequent conversion of the landscape from uncivilized place to colonized space signalled its transformation from the past into the present.[xxxvi] Likewise, by their connection with the pre-colonial landscape, the New World’s Indigenous inhabitants were cast into a temporal condition confined to the prehistoric past. Macneil concludes, “Aboriginality remained defined in terms of colonization’s temporal frontier, as a signifier of the past upon which the colonial nation was built.”[xxxvii] By the late nineteenth century, as artists like those of the Heidelberg school attempted to build a distinct national visuality, Aborigines disappeared almost entirely from Australian art, leaving a melancholy landscape haunted by what Bernard Smith evocatively termed “the spectre of Truganini.”[xxxviii]

And yet, the image of the frontier depicted by Gill in The Newly Arrived and The Colonized is strangely incongruous with this melancholy and empty landscape. Even McLean is forced to note this, offering a curt and unsympathetic dismissal:

If the frontier aesthetic had to first empty the landscape in order to silence it, it also needed to be filled with the figures of the new owners claiming their possession. In this respect, colonial artist S.T. Gill might appear the real precursor of the Impressionist project, as with his The Colonized. However, his satire is in the melancholy vein typical of his time. Gill gives Australia the comic people that he feels it deserves.[xxxix]

While McLean’s explanation seems a considerable development from Bernard Smith’s setting of Gill’s caricature within “melancholy of the Australian scene,” both work on a similar logic, reconciling Gill’s work within what they see as the dominant colonial landscape trope. And yet, it seems to me, that while Gill’s images contain a deep-seated anxiety, this anxiety is markedly different in character to the melancholy of the later Australian Impressionists, or even that of his closer contemporaries such as Eugene von Guérard or Nicholas Chevalier. While Gill moved in the same social circles as von Guérard and Chevalier, he belonged to a markedly different status of artist. The son of a Baptist minister, Gill did not have the benefit of academic training, but rather, was apprenticed as a draughtsman by the Hubard Profile Gallery in London, where he was employed to produce profile silhouettes. After arriving in Adelaide in 1839, he established a studio to produce low cost depictions of humans, animals and houses on “paper suited for home conveyance”[xl] This put him in very different social category of artist from that of von Guérard and Chevalier, who were both academically trained artists who travelled to Australia in search of the exotic and sublime landscape. Unlike the imposing canvases by these artists, Gill’s works were low-cost souvenirs. Tellingly, in 1864 Chevalier’s The Buffalo Ranges 1864 became the first Australian painting acquired by the recently established National Gallery of Victoria; it would be another 90 years before the hallowed institution would acquire a work of ST Gill.[xli]

Nicholas Chevalier, The Buffalo Ranges 1864. Oil on canvas, 132 x 183 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Moreover, despite the efforts of scholars like Geoffrey Dutton and Bernard Smith to reconcile Gill with the landscape tradition that dominates the Australian art historical narrative, Gill’s paintings do not seem particularly interested in the landscape. Gill is a genre painter, and his best works are animated scenes filled with energetic figures. While Smith makes much of the “melancholy” landscape in which these scenes are set, this reading requires a decidedly selective vision. More often than not, the landscape in Gill’s works is little more than a hastily rendered background. Even his most melancholy “outback” scenes, such as those that Gill produced while acting as draughtsman to John Horrock’s ill-fated 1846 expedition, are less concerned with the landscape than the dramatic scene occurring within it (see for instance, Invalid’s tent, salt lake 75 miles north-west of Mount Arden 1846 in the Art Gallery of South Australia). Gill’s great skill was figures, and when he paints an empty landscape, such as Flinders Range, north of Mount Brown c.1846 (Art Gallery of South Australia), the overall effect is far too dull and generic to privilege any particular emotion, melancholic or otherwise. If, as Willis argues, in the art of the Heidelberg school “nature is posited as culture,” it is perhaps unsurprising that Gill’s awkward commercial landscapes were not embraced into the national canon.

ST. Gill. Flinders Range, north of Mount Brown, c.1846. Watercolour on paper, 34.0 x 46.2 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

More significantly, this comparison is illustrative of the connection between modern aesthetics, nationalism and the idealised bush. As Tony Bennett notes, the discourse of aesthetics, which crystallized around this time (centred on emergent institutions like the National Gallery of Victoria, which was founded in Melbourne in 1861) played a significant role in developing new forms of self-governance. This discourse was an “active component in the eighteenth-century culture of taste and played a major role in the subsequent development of the art museum, providing the discursive ground on which it was to discharge its obligations as a reformatory of public morals and manners.”[xlii] By positing nature as culture, while offering their particular vision as the first truly accurate depiction of the Australian landscape, the Heidelberg school perfectly wed modernist aesthetics to this reformatory apparatus.

Tom Roberts, Bailed Up 1895. Oil on canvas, 134.5 x 182.8 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.

Following Marshall Berman, Dipesh Charkrabarty has characterized “modernism” as “designating the aesthetic means by which an urban literate class subject to the invasive forces of modernization seeks to create, however falteringly, a sense of being at home in the modern city.”[xliii] In this context, the retreat from the city by the urbane and educated artists of the Heidelberg school might be seen, as Terry Smith argues, as “ahistorical attempts at ‘universal’ resolutions of conjectures of problems which are threatening the present.”[xliv] Discussing the academic Impressionism of Tom Robert’s Bailed Up 1895 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), Smith concludes:

Roberts’s painstaking realism serves to give to the spectator a sense of being present, at a moment in the past, it gives ‘eyewitness news value’ to history. And it does so [with] the same detachment from the forces of contemporary reality … Conflict between rich and poor, between the rule of law and the rules of the lawless, between the safe system of those who have and the aggressively independent self-seeking of the have-not bushrangers – all this is absent from the painting.[xlv]

![ST. Gill, The King of Terrors and his Satallites [sic], c.1880. Watercolour, 31.7 x 22.2 cm. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.](https://henryfskerritt.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/img001-copy.jpg?w=214&h=300)

ST. Gill, The King of Terrors and his Satallites [sic], c.1880. Watercolour, 31.7 x 22.2 cm. State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

ST Gill, A City of Melbourne Solicitor 1866, lithograph, 34 x 26.6 cm, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

When Gill arrived in Melbourne in 1852, the Victorian gold rush had just begun transforming the city from a small, provincial town into one of the world’s richest metropolises. Although he found little success as a miner, Gill made a roaring trade selling images of the goldfields to the influx of men and women who flocked to north-eastern Victoria from across Australia and the world. In his four years in Melbourne, Gill documented life of the goldfields with an unmatched vigour and animation. In 1856, he left Melbourne in order to try and extend his artistic success into New South Wales; when he returned in 1864 he found a city transformed. In the decade since his arrival in Melbourne, the population had risen from 23,000 in 1852 to over 140,000 in 1861. Over 20 million ounces of gold had been mined from the Victorian goldfields, allowing for the construction of grand new buildings, roads, modern plumbing and gas lighting, ushering in the era of “Marvellous Melbourne.”[xlvii]

Suffering from financial difficulties, alcoholism, and venereal disease, Gill was perhaps indisposed to celebrate the city’s new-found prosperity. The images that he produced in his final decades in Melbourne present an unremittingly bleak view of the modern city, lacking the levity of humour of his images of the goldfields; a vision of modernity characterised by public drunkenness, racial degradation, alienation and poverty. This might well have reflected Gill’s internal state, but it should also be seen as an indication of the radical acceleration of modernity that occurred in Melbourne in the 1850s and 60s. As Bennett notes in regards to the slowly unfolding influence of evolution and historicism in Australia, modernity arrived in gradual waves: a “slow modernity” rather than a rupture.[xlviii] Unlike the Heidelberg artists, who were mostly born in the decade after 1865, Gill witnessed firsthand the maturation of modernity in Australian cities; the fully-fledged modernity that characterized the grand metropolis of Melbourne in the 1880s should not, therefore, be assumed to be a naturalized part of Gill’s understanding of the world.

ST Gill, On the Board of Works 1866, lithograph, 34 x 26.6 cm, University of Melbourne Art Collection.

A simple analogy might be seen in his preferred choice of medium: the watercolour ‘sketch.’ In 1845, Gill had acquired a daguerreotype, the first camera in the colony of South Australia. The purchase was greeted with great enthusiasm in Adelaide, with the South Australian Register noting:

It appears to take likenesses as if by magic. The sitter is reflected in a piece of looking glass, and suddenly, without aid of brush or pencil, his reflection is “stamped” and “crystalised.” That there should be an error is absolutely impossible. It is the man himself. The portrait is, in fact, a preserved looking glass.[xlix]

Gill’s career as a photographer was, however, short lived, and soon after acquiring his daguerreotype machine, he sold it to the publican Robert Hall.[l] The most likely reason for this was financial; it was not until the late 1890s that new printing processes made photographic reproduction an affordable medium of dissemination.[li] On a psychic level, however, Paul Carter notes that the realism of photography – as marveled by the reporter from the South Australian Register – created an “ambiguity of the present tense” that undermined the colonizer’s ontological claims of spatial speculation, as it presented a history of objects (“the man himself”) rather than their conjuration by discovery. This could only be resolved by returning to the picturesque view of the tourist: “The strangest place in this looking glass world is where we stand looking into it but fail to see ourselves reflected there, glimpsing instead the strangeness of our origins.”[lii]

In abandoning the photographic for the painterly, Gill might be seen to be playing precisely into this colonial trope, preempting the Heidelberg artist’s claim to capture the essential truth of the landscape. Indeed, this is not far from Dutton’s interpretation, that in the watercolor sketch, Gill found the medium best suited to his desire to capture the liveliness and spontaneity of colonial life.[liii] And yet, Gill did not abandon photography (the most modern and mimetic mode available) in order to adopt the picturesque stylings of Chevalier of von Guérard; he abandoned photography in favor of the debased popular medium of caricature.

ST Gill, The Provident Diggers 1869. Watercolor, 26.8 x 19.5 cm, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

While Gill’s first volume of published sketches purport to represent his subjects precisely “as they are,”[liv] the image’s mode as satire offers a markedly different version of presentness to the “eyewitness news value” of the Heidelberg artists. This is most strikingly evident in Gill’s use of paired images, such as The Newly Arrived and The Colonized, or the pair of lithographs The Provident Diggers in Melbourne and The Improvident Diggers in Melbourne which appeared in Gill’s 1852 publication The Victorian Gold Diggings and Diggers as They Are. The folly of reading these images as documentary is illustrated by Graeme Davison, who completely fails to recognize the irony of Gill’s depiction of the diggers, reading them as straightforward morality pieces:

Conservative colonists feared … that the social dislocation of the gold rush might culminate in anarchy and revolution. The arrival of thousands of avaricious young men, adrift from the restraining influence of home and kin, exposed to the hazards and temptations of frontier life and susceptible to the appeals of radicals and revolutionaries, inspired dread among the governing classes. S.T. Gill gave vivid expression to these fears in his contrasting portraits of the ‘improvident digger’, bent upon riot and debauchery, and the ‘provident digger’ contemplating self-advancement and domesticity.[lv]

While Gill’s “improvident diggers” are shown drunkenly staggering past a jewelry store, the “provident” pair soberly concentrate on plans for available freehold land displayed in a realtor’s window. And yet, like many of Gill’s images, the message of this counterpoint is far from straightforward. As most contemporary Australian viewers would have been aware, inflation and land shortages had created a situation in which private real-estate contractors could easily prey upon unwitting diggers, charging highly inflated prices for low quality holdings. In such a situation, gold was a much sounder investment. In this situation, it was the “provident” digger was the one most likely to be swindled.

ST Gill, The Improvident Diggers 1869. Watercolor, 26.8 x 19.5 cm, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

To read Gill’s images as morality tales, as Davison does, is to quite literally miss the joke. As Geoffrey Dutton rightly asserts, “S.T. Gill was a humourist rather than a moralist.”[lvi] However, as Rex Butler and Ian McLean note”

A joke gets its laughs by momentarily revealing the absurdity of a conventional truth, as in the medieval carnival that turns the world upside down. The secret is not to resolve the antinomy but hold it in suspense; what Žižek calls a parallax view. Thus the successful mimic is always funny because they are two at once.[lvii]

This is particularly significant, considering the dual nature of Gill’s audience; The Victorian Gold Diggings and Diggers as They Are was editioned in both Australia and Britain, and was therefore required to appeal to both colonial and imperial tastes.[lviii] And yet, as Žižek notes, the joke also serves to transform an inherent limitation (that which cannot be spoken, the position that cannot be assumed, the void of what cannot be seen from the first perspective, the space between The Newly Arrived and The Colonized) into something that is only a contingent difficulty that will one day be overcome. Nowhere is this ambiguity more evident than in one of Gill’s most difficult and troubling works: Native Dignity 1866.

Samuel Thomas (ST) Gill, Native dignity 1866, lithograph, The University of Melbourne Art Collection, Gift of the Sir Russell and Mab Grimwade ‘Miegunyah’ Bequest, 1973, 1973.0648

By the mid-1860s, orthogenetic theories of social evolution were slowly beginning to emerge in Australia.[lix] Aboriginal culture was seen as an earlier stage in the teleological progress of human civilization and likened to an archaeological remnant of primeval man. Once contact was made with the more ‘advanced’ cultures, it was assumed inevitable that this ‘primitive’ culture would disappear. Not only did this lead to a sense of urgency on the part of early anthropologists to record and collect ethnographic data for the information it could shed on the development of humanity, but it inspired artists like Gill to create detailed visual records of Indigenous dress, material objects and cultural practices. He documented these observations in his most lavish publication, The Australian Sketchbook 1865.[lx]

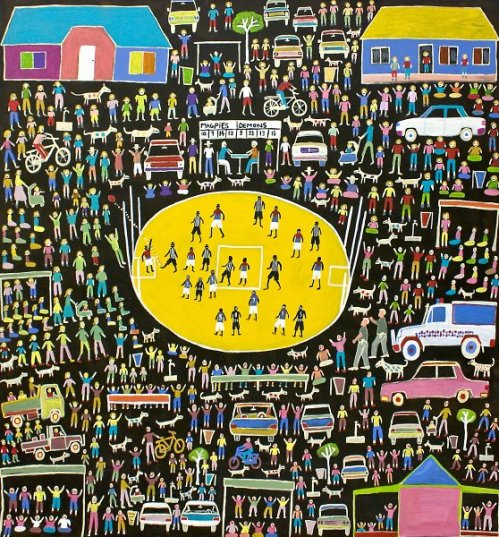

In contrast to the detailed attention paid to traditional Indigenous dress and custom in The Australian Sketchbook, Native Dignity offers a striking counterpoint. An Aboriginal man is shown in a battered top hat, cutaway jacket and shirt, but no trousers. With his cane under his arm he swaggers down the street, alongside a smiling female companion swishing a tattered crinoline and a dinky parasol. It is likely that Gill, like many of his contemporaries saw Indigenous Australians as a dying race, but Native Dignity might also be seen as a critical commentary on the adverse impact of the encroachment of modernity upon both Indigenous and non-indigenous subjects in the colonial city. In making this claim, it is worth revisiting Edmonds assertion that the colonial city was a charged site in which “issues of civilization and savagery; race, gender and miscegenation were played out.”[lxi]

By the 1860s, images of Indigenous Australians in the urban setting were increasingly rare, not because Indigenous Australians were not present in Australian cities, but because their presence was a source of great anxiety amongst non-indigenous Australians. As Patrick Wolfe argues, rather than a fixed site, the frontier was always shifting, contextual and negotiated: always placing the Aboriginal somewhere else.[lxii] Lynette Russell continues, “the spatial coexistence of invaders and indigenes was anomalous making settler colonialism an assertion about the nation’s structure rather than a statement about its origins.”[lxiii] Beyond a simple racist stereotype, by picturing Indigenous people in the present, in such an ambiguous image of the urban frontier, Native Dignity plays upon the full range of urban anxieties of the non-indigenous colonial subject.

Confronted with the realities of the urban frontier, the settler subject is forcibly cast into the role of both colonizer and colonized in a dialectic of domination in which the self and the Other become mutually dependent. Although imbued with all the prejudices of its time, the very act of picturing this violence is, in some small and unintentional way, a form of resistance to the imperialism of silence. As Lynette Russell concludes, “when frontiers and boundaries are examined closely they seem to melt away. Instead of a line or a space or even a contact zone, we find only a concept, a notion that lacks temporal and geographic specificity.”[lxiv] Rather than defining the Australian experience, in Native Dignity, the melancholy nationalist landscape tradition fades into the dust between barefoot dancing feet.

[i] Lynette Russell, ed. Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 4.

[ii] Ian McLean, “Under Saturn: Melancholy and the Colonial Imagination,” in Double Vision: Art Histories and Colonial Histories in the Pacific, ed. Nicholas Thomas and Diane Losche (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 152-58.

[iii] Paul Carter, The Road to Botany Bay (London: Faber and Faber, 1987), 154-55.

[iv] Rex Butler, ed. Radical Revisionism: An Anthology of Writings on Australian Art (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2005), 9.

[v] Homi K. Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,” October 28(1984): 126-7.

[vi] Penelope Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers: Indigenous Peoples and Settlers in 19th-Century Pacific Rim Cities (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010), 5-6.

[vii] Ibid., 9.

[viii] Ibid., 10.

[ix] Keith Macrae Bowden, Samuel Thomas Gill: Artist (Maryborough: The Author, 1971), 103-12; Geoffrey Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia (South Melbourne: Macmillan, 1981), 47-50.

[x] Ibid., 7.

[xi] A.W. Greig, “An Australian Cruikshank,” The Argus, Saturday 14 September 1912, 7. Reprinted in The Register, Wednesday 18 September 1912, 11.

[xii] Bowden, Samuel Thomas Gill: Artist, 109.

[xiii] See for instance, William Moore, The Story of Australian Art (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1934), 59-60. Bernard Smith, Place, Taste and Tradition (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1945), 67-70; Bernard Smith, Terry Smith, and Christopher Heathcote, Australian Painting 1788-2000 (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001), 49-53. Gill was also routinely featured in Australian newspapers and art magazines, for instance, E. McCaughan, “Samuel Thomas Gill,” The Australasian, 15 November 1930. Basil Burdett, “Samuel Thomas Gill: An Artist of the ‘Fifties,” Art in Australia 3, no. 49 (1933); W.H. Langham, “Samuel Thomas Gill (1818-1880): Landscape Painter,” Bulletin of the National Gallery of South Australia 2, no. 1 (1940); J.K Moir, “S.T. Gill, the Artist of the Goldfields,” The Argus, 9 December 1944 1944.

[xiv] Bowden, Samuel Thomas Gill: Artist, xi.

[xv] Anne-Marie Willis, Illusions of Identity: The Art of Nation (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1993), 62.

[xvi] Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia, 7.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Willis, Illusions of Identity: The Art of Nation.

[xix] Ibid., 62-64.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Smith, Place, Taste and Tradition, 67.

[xxii] Ibid., 67-70.

[xxiii] Richard White, Inventing Australia (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1981), 106.

[xxiv] Smith, Smith, and Heathcote, Australian Painting 1788-2000, 50.

[xxv] Ibid., 50-51.

[xxvi] Bernard Smith, The Spectre of Truganini: The 1980 Boyer Lectures (Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1980).

[xxvii] McLean, “Under Saturn: Melancholy and the Colonial Imagination,” 131-42.

[xxviii] Ibid., 136-7.

[xxix] Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in The Froniter in American History, ed. Frederick Jackson Turner (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1921), 3.

[xxx] Ibid., 4.

[xxxi] Carter, The Road to Botany Bay, 158.

[xxxii] David Hamer, New Towns in the New World (New York: Columbia University, 1990), 65.

[xxxiii] Carter, The Road to Botany Bay, 136.

[xxxiv] The maintenance and hegemony of this identity position is taken up by a number of scholars, for example Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 14-15; Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 16-17.

[xxxv] As Johannes Fabian observes, “there is no knowledge of the Other which is not also a temporal, historical and political act.” Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983; repr., 2002). Similar positions are articulated in Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference; Tony Bennett, Pasts Beyond Memory: Evolution, Museums, Colonialism (New York: Routledge, 2004).

[xxxvi] Rod Macneil, “Time after Time: Temporal Frontiers and Boundaries in Colonial Images of the Australian Landscape,” in Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies, ed. Lynette Russell (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 48-49.

[xxxvii] Rod Macneil, “Time after Time: Temporal Frontiers and Boundaries in Colonial Images of the Australian Landscape,” in Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies, ed. Lynette Russell (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 49.

[xxxviii] Truganini (c.1812-1876) was an Aboriginal woman from the island of Tasmania. By the time of her death, she was widely considered the “last full-blooded Aboriginal Tasmanian.” Smith, The Spectre of Truganini: The 1980 Boyer Lectures.

[xxxix] Ian McLean, “Picturing Australia: The Impressionist Swindle,” in Becoming Australians: The Movement Towards Federation in Ballarat and the Nation, ed. Kevin T. Livingston, Richard Jordan, and Gay Sweely (Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press, 2001), 59.

[xl] E.J.R. Morgan, “Gill, Samuel Thomas (1818-1880),” in Australian Dictionary of Biography (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1966); Patricia Wilkie, “For Friends at Home: Some Early Views of Melbourne,” La Trobe Journal 46(1991).

[xli] In 1954, the National Gallery of Victoria purchased their first work by Gill, The Avengers c.1869.

[xlii] Bennett, Pasts Beyond Memory: Evolution, Museums, Colonialism, 3.

[xliii] Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, 155-56. See also, Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air (New York: Penguin, 1988), Ch. 1.

[xliv] Terry Smith, Transformations in Australian Art: The Nineteenth Century: Landscape, Colony and Nation (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002), 93.

[xlv] Terry Smith, Transformations in Australian Art: The Nineteenth Century: Landscape, Colony and Nation (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002), 99. In noting this disconnect from the urbanized reality, Smith notes, “In this sense it is a retrospective creation, celebrating a phase which was passing. And, in this same sense, it is city-based: it imposes the over confident optimism of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ onto a declining rural industry … There is no suggestion here that Roberts is deliberately misrepresenting the situations he is painting: all of them, with the exception of the bushranging subjects, could be witnessed in places throughout Australia. Rather, interest lies in the fact that, unlike much of the popular illustration and public rhetoric of the time, he elects not to show the most progressive aspect of the situation.” 84-85.

[xlvi] Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia, 27.

[xlvii] Graeme Davison, The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne (Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2004).

[xlviii] Bennett, Pasts Beyond Memory: Evolution, Museums, Colonialism.

[xlix] South Australian Register, Saturday November 8, 1845, 2.

[l] Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia, 18.

[li] Wilkie, “For Friends at Home: Some Early Views of Melbourne,” 64.

[lii] Paul Carter, Living in a New County: History, Travelling and Language (London: Faber, 1992), 36-45.

[liii] Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia, 18-19.

[liv] Samuel Thomas Gill, The Victoria Gold Diggings and Diggers as They Are (Melbourne: Macartney & Galbraith, 1852).

[lv] Graeme Davison, “Gold-Rush Melbourne,” in Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia, ed. Iain McCalman and Alexander Cook (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 63.

[lvi] Dutton, S.T. Gill’s Australia, 28.

[lvii] Rex Butler and Ian McLean, “Let Uz Not Talk Falsely Now,” in Richard Bell: Lessons on Etiquette and Manners, ed. Max Delany and Francis E. Parker (Caufield East, Victoria: Monash University Museum of Art, 2013), 39.

[lviii] As I have argued elsewhere, in Britain, the display of colonial iniquity was a subject of considerable interest, playing up to both Imperial fantasies of domination and colonial anxiety. Henry Skerritt, “William Strutt: Bushrangers, Victoria, Australia, 1852,” in Visions Past and Present: Celebrating 40 Years, ed. Christopher Menz (Parkville, Victoria: Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 2012).

[lix] Phillip Jones, “Words to Objects: Origins of Ethnography in Colonial South Australia,” Records of the South Australian Museum 33, no. 1 (2000).

[lx] Samuel Thomas Gill, The Australian Sketchbook (Melbourne: Hamel & Ferguson, 1865).

[lxi] Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers: Indigenous Peoples and Settlers in 19th-Century Pacific Rim Cities 12.

[lxii] Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology (London: Cassell, 1999), 173.

[lxiii] Russell, Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies, 2.

[lxiv] Ibid., 11-13.