The following review appeared in Art Guide Australia, January/February 2013, 68-72.

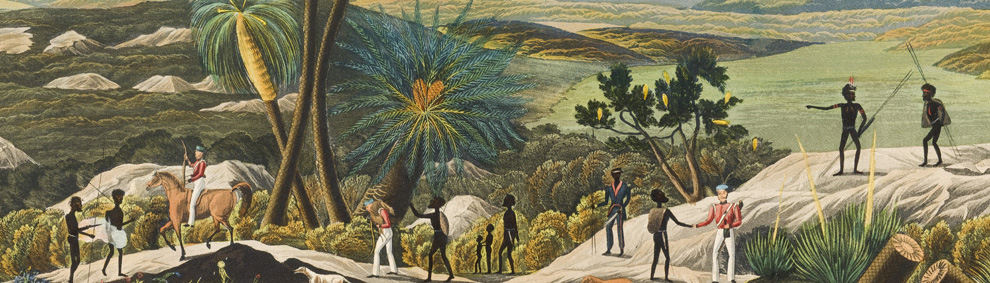

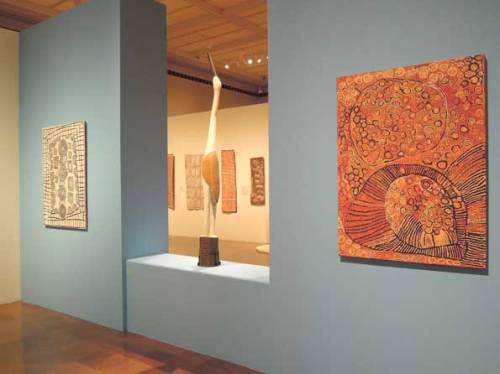

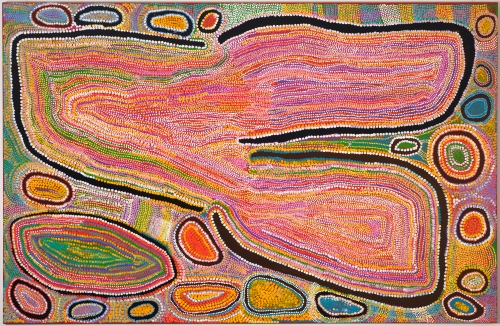

Installation image from Crossing Cultures: The Owen and Wagner Collection of Contemporary Aboriginal Australian Art at the Hood Museum of Art.

In his recent compendium, How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art, Ian McLean observes that the rise to prominence of Aboriginal art in the 1980s was due, in no small part, to timing. Buoyed by the radical ideas that percolated in the 1960s and 70s, a younger generation of artists and critics sought out more performative and visceral modes of art production, to which Aboriginal art seemed a perfect fit. At the same time, these formally brilliant canvases (with their uncanny visual affinity to late modernist abstraction) also appeased the desires of nostalgic modernists, hoping that these desert prophets could reinvigorate the formalist tradition. McLean is rightly dismissive of this latter tendency: “Whatever cheer modernists may have got from Papunya Tula painting, its artworld ascendency was only possible because of the perceived exhaustion of modernism. Whatever its transcendental beauty, Papunya Tula painting did not rescue modernism, but discovered a way for painting to continue after it.”[i]

I write this from Pittsburgh, the once famed industrial centre in the rust-belt of the north-east United States. It is a city that has played its own small part in the development of contemporary art: it is the birthplace of Andy Warhol and the Carnegie International, which since 1896 has been one of the world’s longest running contemporary art exhibitions. It is also a city in which the realities of the end of modernity and Euro-American industrial dominance are unmistakably evident. In the ruins of a once thriving steel industry, it is a city that has been reborn in the model of 21st century globalism; its economy structured around universities, medical technologies and IT companies like Google whose worker-friendly offices inhabit a former factory on the city’s revitalised east end.

Abie, Loy Kamerre, Bush Hen Dreaming, Sandhill Country, 2004, Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 71 5/8 x 71 5/8 in, Seattle Art Museum, Promised gift of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan.

2012 has been a pretty big year for Aboriginal art in America; it would be an overstatement to suggest that it stormed the citadels of contemporary art in the USA, but two major exhibitions on opposite sides of the country asserted the global significance of the Australian Indigenous art movement. On the west coast, Ancestral Modern at the Seattle Art Museum (May 31-September 2) exhibited the promised bequest of collectors Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan, while in New Hampshire, Crossing Cultures at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College presented the equally beneficent gift of collectors Will Owen and Harvey Wagner (September 15, 2012 – March 10, 2013).

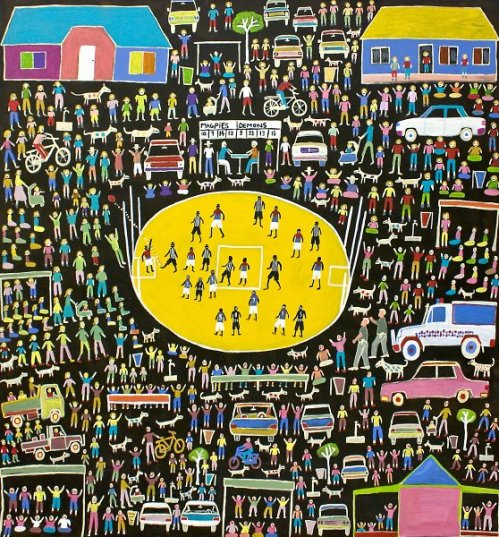

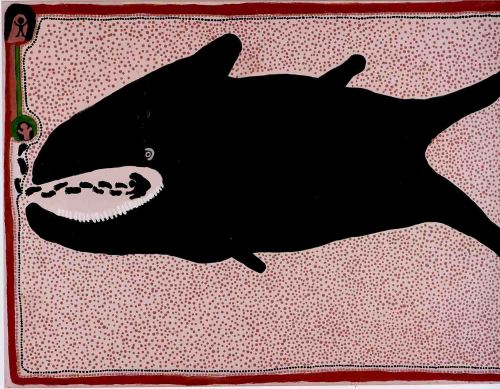

Both exhibitions presented a radiant picture of the strength and diversity of contemporary Indigenous art practice in Australia, with their differences resting mostly in the peculiar strengths of the collectors’ respective visions. For Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan, the collection was the result of a premeditated desire to create a “museum-quality collection.”[ii] As a result, Ancestral Modern was dominated by large, abstract works, highlights of which included a spectacular canvas by Mitjili Napanangka Gibson, a commanding collaborative painting by the Spinifex Mens Collaborative, and a judicious selection of elegant works from Utopia in the Eastern Desert; a potent reminder of the formidable power of these artists before many fizzled into a repetitive artistic paralysis. And yet, it would be wrong to characterise Ancestral Modern as only presenting the abstract, modernist-eque tendencies of contemporary Aboriginal art; the exhibition was punctuated with wonderfully surprising figurative works by Alan Griffiths, Jarinyanu David Downs and Stewart Hoosan, all of which helped present a vibrant picture of contemporary artistic practice in remote Australia.

Installation image of Crossing Cultures at the Toledo Museum of Art, showing Patrick Tjungarrayi’s Illyatjara 2001 (left) and Naata Nungurrayi’s Marapinti 2005 (right).

In contrast to Ancestral Modern, most of the works in Crossing Cultures were domestic in scale, reflecting the more modest aspirations with which Will Owen and Harvey Wagner assembled their collection. Nevertheless, their collection has grown to be almost encyclopaedic in scope, and despite their modest size, works like Patrick Tjungarrayi’s Illyatjara 2001 (121 x 91 cm) or Naata Nungurrayi’s Marapinti 2005 (121 x 91 cm) are expansive in their aesthetic achievements, proving that quality always trumps scale. But the real strength of both exhibitions lies in the extraordinarily coherent visions brought to their collections by these very different collectors. In both exhibitions, the tastes, aspirations and passions of the collectors was readily apparent, allowing the sensitive curating of Pamela McClusky and Stephen Gilchrist to tease out rich parallels within both collections. Both exhibitions were accompanied with substantive catalogues (for the sake of disclosure I should note that I provided one of the ten catalogue essays for Crossing Cultures) and a rich program of talks and symposia, which brought together leading thinkers in the field from Australia and abroad.

At both these symposia, the overriding question seemed to be how to capitalize upon the success of these shows: how to stake Aboriginal art a central position in the global narrative of contemporary art. Those who gathered took for granted that the art of Aboriginal Australia is some of the most serious and important work being produced in the world today. The difficulty, it would seem, was communicating this to the rest of the world. When reflecting on these two shows, and their reception in the USA, I am inclined to return to McLean’s analysis, to wonder whether the battle for the critical soul of Aboriginal art has been adequately resolved. For instance, in one of the more lengthy critical reviews of Crossing Cultures, art critic Kyle Chayka begins with the question “Is Aboriginal Abstraction Modernist?”[iii] While Chayka’s review is thoughtful and perceptive, there is a staggering Eurocentrism in the insistent tendency to frame Aboriginal art in these modernist terms. In the 1980s, Aboriginal art was discussed critically in terms of postmodernism, conceptualism, performance and land-art. Thirty years later, we seem stuck ad-nauseum on the fabled tale of when Rover Thomas thought a Mark Rothko looked vaguely like his, or how much Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s work looks a bit like a Jackson Pollock. These are specious formal comparisons that neuter Aboriginal art into an outdated visual regime.

Jarinyanu David Downs, Whale Fish Vomiting Jonah 1993, acrylic on canvas, 112 x 137 cm, Seatle Art Museum, promised gift of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan.

The persistence of such comparisons cannot be attributed to a paucity of good criticism; at the present, many of the finest minds in Australian art history, anthropology and journalism are turning their pens to Australian Aboriginal art with increasing sophistication. One can only presume that more insidious motives are at play. As McLean notes, modernism is exhausted, but this cannot prevent it clinging to the crumbling residues of its power, attempting to exert the supremacy of a centre that looks increasingly Ozymandias-like. Aboriginal art is not simply a defence mechanism against the onslaught of colonialism, it is a powerful weapon that exposes the contradictions and antinomies inherent in the modernist imperial project. This is why Aboriginal art stands at the vanguard of contemporary art: it is able to express the coevality of difference, while maintaining its own identity; to show the coexistence of multiple ways of being in the present; and to reveal the connective fibres of relation that make the contemporary world comprehensible. Aboriginal art shows us what it means to live in a world of accelerating multiplicity – literally, what it means to be contemporary.

So what is the solution? Firstly, we need a forceful definition of contemporary art: one in which modernism is merely a single possibility, neither more inevitable nor valuable than any other.[iv] Secondly, there is an urgent need for curators to begin working across the fields of Indigenous and non-indigenous art, in order to move beyond superficial visual affinities towards serious conceptual engagements. In the catalogue for Ancestral Modern, the curator Lisa Graziose Corrin attempts precisely this task in a way that it rarely encountered. In comparing the work of artists like Mawukura Jimmy Nerrimah and Mitjili Napanangka Gibson to contemporaries like Julie Mehretu and Raqib Shaw, Corrin attempts to create ‘conversations’ in which the expressive and conceptual forcefulness of Aboriginal art is able to participate in a truly planetary conversation. This is a far cry from the often limp politeness with which Aboriginal art is so often included in Australian biennials and group exhibitions.

Mitjili Napanangka Gibson, Wilkinkarra 2007, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 305 cm, Seattle Art Museum, promised gift of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan.

It is time for curators to begin thinking in these planetary terms. It is shameful how few curators in Australia are working across the fields of Indigenous and non-indigenous contemporary art. Aboriginal artists have long been engaged in this conversation, offering a munificent cross-cultural dialogue with the non-indigenous world, through which the strength and vitality of their culture has been displayed with ever increasing aesthetic poise and finesse. This is the brilliant lesson of exhibitions like Ancestral Modern and Crossing Cultures; judging from their popularity, it is a lesson that has been warmly received in the USA. Most importantly, through the generosity of these collectors, there are now three significant collections of Aboriginal art in the United States (the third being the Kluge-Ruhe collection at the University of Virginia). Aboriginal art might not have stormed the barricades yet, but these collections are like splinter cells, biding their time ready to strike.

[i] Ian McLean, How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2011): 44-47.

[ii] Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, “Collectors’ Statement,” in Pamela McClusky, ed., Ancestral Modern: Australian Aboriginal Art (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2012): 11.

[iii] Kyle Chayka, “Is Aboriginal Abstraction Modernist?” Hyperallergic, October 16, 2012.

[iv] See for instance, Terry Smith, What is Contemporary Art? (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009).